Trip report: Cape Wrath Trail

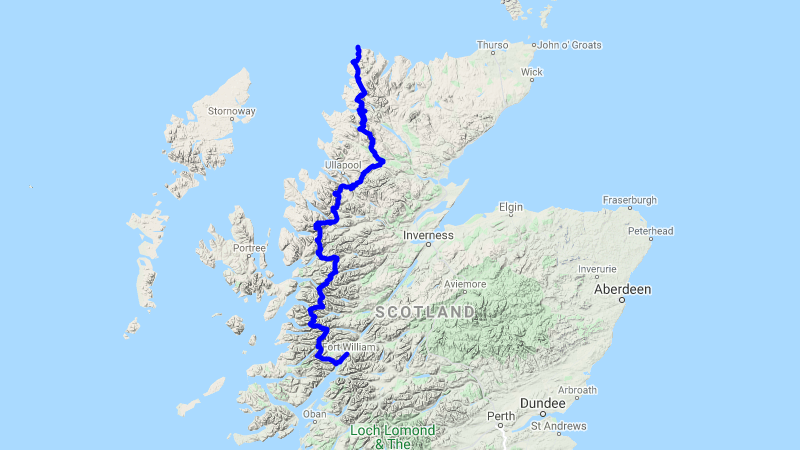

The Cape Wrath Trail is an approximately 350 km (220 mi) walk through the Scottish Highlands, stretching from Fort William to the northwesternmost point of mainland Britain, Cape Wrath. The route is unmarked and there is no official line. It has the reputation of being Britain’s toughest long distance walk.

In the fall of 2020 I hiked the Cape Wrath Trail solo in eleven days. This trail already has its share of uncertainty, but the global pandemic raging in the background brought a few more.

Most people recommend walking the trail in May or early June. This gives the best chance of fair weather while still avoiding the midges. That timing didn’t work for me, so I went in late September (again to avoid the midges, of which I encountered only a few). September has some unique challenges that aren’t present in May.

One is that fall is deer stalking season in Scotland. This means that some bothies are locked. Actually, the Mountain Bothies Association website was reporting that all bothies were closed due to the pandemic. I didn’t find this to be true—more than half of the bothies I found along the way were open, and I ended up sleeping in two. Deer stalking season also means that you need to stick to the trails, but it didn’t appear to be much of an issue for Cape Wrath walkers (as opposed to Munro bagging, for example).

A stag I spotted near Loch an Leathaid Bhuain.

A stag I spotted near Loch an Leathaid Bhuain.

The second bit about fall is that there is much less daylight. I used most of the daylight hours for walking, and didn’t have much left for anything else. Even if your body has adapted to longer mileage, doing big days is hard in fall unless you’re willing to hike in darkness.

The trip

At twelve o’clock on 2020-09-19 I got on a train at London Euston station. After some fish & chips and a pint in Glasgow and a brief stop in Crianlarich, I arrived in Fort William, Scotland a bit more than ten hours after I’d started. The only open hostel I had found wasn’t accepting solo travelers due to the pandemic, but I was able to reserve a spot at the campground in Glen Nevis, a 4 km walk from town.

In the morning I decided to climb Ben Nevis as a warmup. It was cold with very limited visibility at the summit, so I was back down at the campsite by noon.

The following day I packed up early and got the 7:30 ferry to Camusnagaul, officially starting the Cape Wrath Trail. I was the only one on board. This ferry trip meant I was doing the Glenfinnan / Knoydart variant of the route, which is apparently more difficult but also more rugged and beautiful. I can attest that Knoydart has some of the most rugged and beautiful scenery of the whole trail.

Naturally, it started to rain shortly after I got off the ferry. In a fitting start to the Cape Wrath Trail, I experienced the worst weather of the trip on the first day, with driving rain and wind.

While the first 20 km were on road and hard packed track and easy going, after I climbed the first mountain pass it quickly became clear what kind of conditions I could expect over the coming 300+ km.

The continuous rain had turned the trail into a shallow stream, punctuated by long muddy sections with rocks. This went on for a whole valley, with a river accumulating water down below.

Footwear

I chose to wear trail runners instead of waterproof boots. Even the best waterproof boots will fail in sufficiently bad conditions (e.g. my first day), so they’re only delaying the inevitable: wet feet. I’ve heard of plastic bag tricks, but I ended up sinking knee or thigh deep into a marsh often enough that this too would not have saved me. Not to mention the sweat. It’s best to embrace the wetness: trail runners walk lighter, faster and can at least dry out given the opportunity.

I think I made the right choice—my boots would have soaked through on the first day and remained wet for the rest of the trip. I should note that my trail runners also did not dry overnight, but did while walking in dry conditions. In general, things just don’t dry very well in the western Highlands.

All of the gear I brought.

All of the gear I brought.

I rotated two pairs of socks for walking, letting one pair air out on the outside of my pack. I also brought an extra pair of dry socks for inside my tent. In general I tried to air out my feet whenever the weather permitted it. It required some careful management, but with enough preventive tape and compeed I only ended up with two minor blisters the entire walk.

Near the end of the first day I got to a river crossing, where I saw three fellow CWT hikers. One had already crossed. One was taking a picture, while the last was taking off his shoes and socks at the edge of the river, presumably in order to cross.

The river was approximately 4 meters wide, a bit more than knee deep and rather fast flowing. My socks and shoes were obviously already soaked through, and my hiking and rain pants were wet and covered with mud. So I went ahead and crossed without hesitation. The current was quite aggressive, but by facing upstream and planting my feet and trekking poles carefully I made it across without feeling like I was in any significant danger.

Once on the other side, I chatted to the guy already across. The nice thing about being on trail is that even as an introvert, you end up talking to everyone you see (which ended up being one or two people a day). Everyone is very friendly and interested in what you’re doing and where you’re from, especially solo travelers. This trio was from Germany, and they were on the second day of their Cape Wrath Trail hike.

While we were talking, the other guy threw one of his shoes across the river, which I had to dodge. A bit later he threw his second one, underhand. He held on a bit too long, and we all watched in horror as his shoe flew into the air in a perfect parabolic arc, landing exactly in the middle of the river. The river took the shoe immediately and swept it away.

I was stunned. The other guy was too! A few seconds later we took a shortcut to the river bank downstream, just in time to see the shoe go over the top of a waterfall and disappear forever. I was still in shock at the series of poor decisions that led someone to throw their only shoe into a river. The other guy evidently felt the same way, since he asked his friend “what the hell were you thinking?” in an exasperated manner.

Finally he told me to have a good trip while they would try to figure out how to salvage the situation. This experience taught me an important lesson about crossing fast flowing rivers. Don’t take off your footwear!

I think this river would have been a small, easily passable stream on a dry day. It turns out that the trail is very variable in this way—speaking to fellow hikers, small tributaries I easily stepped over on dry days were dangerously fast flowing rivers in spate.

I continued on in the rain for a few hours more and found a suitable campsite a bit north of the Glenfinnan Viaduct of Harry Potter fame.

Sleeping

I spent all but two nights in a tent. One reason is that many lodges along the route appeared to be closed due to the pandemic. But the real reason is that I like camping, and I like the freedom of being able to sleep wherever I want. The other two nights I spent in bothies, just to get the full Cape Wrath Trail experience.

The tent I brought was the Tarptent Notch. It’s a very lightweight, double-walled one person tent that uses trekking poles to set up. I was extremely happy with it—it’s arguably a perfect tent for this type of trip.

Beside the tent, I had the standard setup: down sleeping bag rated to -2°C, lightweight air mattress, inflatable pillow. Ultralight backpackers will balk at this, but I actually brought a second folding mattress. I really like having something clean to sit or lie on during breaks, and in the evening outside my tent. I could probably have cut it down to size though.

The weather on my second day was fantastic. After climbing the first mountain pass of the day, I got to a long section without any trail at all.

Looking southwest from the mountain pass between Sgùrr Thuilm and Streap.

Looking southwest from the mountain pass between Sgùrr Thuilm and Streap.

Navigation

My primary mode of navigation was by physical map. Harvey Maps have managed to fit the whole trail on just two maps at 1:40000 scale. At that scale you do miss some details, meaning it can often be difficult to pinpoint exactly where you are (especially when there is no trail).

In this case, navigation was easy since I was traveling down a narrow valley. But in general I needed a way to get my location on the map. I was hoping to use a GPS spot device for this, but it turns out that the Garmin inReach Mini I had borrowed does not give you a way to convert latlon to UK national grid references (which the Harvey and OS maps use). Luckily I was able to find an app on my phone to give my grid reference for me, and that worked really well.

I also brought a compass to take bearings. I rarely needed to do this, but it was quite useful in some of the longer trail-less stretches with fewer features. With this system, I rarely ended up taking a wrong turn, and there was only one time that I lost more than 5 or 10 minutes doing so.

Since I did the trip alone and large parts of the trail are outside cell service, I did bring the spot device. In remote mountain areas, a small accident can easily escalate to a life threatening situation.

I found the sections with intermittent or no path at all (and even many sections with a path) generally slow going. The Cape Wrath Trail isn’t technical, but it is a slog in many parts and you can’t always expect to cover the distance you would be able to on dry and well groomed trail. I think I averaged approximately 32 km (20 mi) a day, in part because there just wasn’t enough daytime to do more (but also because I was tired).

I got to Shiel Bridge on the morning of the fourth day, where I was hoping to resupply and get a hot meal.

Food

From what I’ve heard, a lot of people send packages of food ahead. This is probably a good idea, especially if there’s a pandemic and you aren’t sure if places are open. I didn’t do that. But I did bring some backup freeze-dried meals and bars, just in case.

I didn’t end up needing them, since I was able to resupply in Shiel Bridge (day 4), Kinlochewe (day 6) and Kinlochbervie (the last day, 11). In Shiel Bridge, the petrol station I was looking to resupply at was closed, but luckily Kintail Crafts was open and had a limited but good selection of items. Kinlochewe’s petrol station was similar (and served good sandwiches and soup!).

The only two times I was able to get a real meal were in Strathcarron (day 5) and Kinlochbervie. Most trip reports I’ve read saw people eating at multiple lodges and pubs along the way, but for me nearly everything was closed, either due to the pandemic or just poor timing.

Instead, I usually ate oatmeal for breakfast (using a large supply of milk powder I brought from home). Lunch and dinner were usually instant noodles or pasta. This was supplemented with a lot of bars, Scottish shortbread and cookies throughout the day. I was also able to get some fruit.

My cooking setup was a 900 mL pot, a small stove and a 230 g gas canister. I actually brought two because I wasn’t sure if I would be able to find any on the trail (I didn’t see any until Kinlochbervie). But as it turned out I only needed one. It ran out as my last pot of water came to a boil—that’s 11 days of use for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

Between Strathcarron and Kinlochewe, I crossed over a fairly high mountain pass, and camped near Loch Coire Làir.

My view of Beinn Eighe and friends, before crossing over a mountain pass.

My view of Beinn Eighe and friends, before crossing over a mountain pass.

This was the coldest night I experienced. In the morning, I found frost on the tips of my tent, ice on the inside of my pot and a thin layer of ice on the ponds around me.

Staying warm

During the day temperatures usually hovered around 10–15°C, and I got by with merino wool underwear and shirt, lightweight hiking pants and a midlayer fleece. It got colder in wet conditions, and the addition of rain gear was usually enough to keep me warm (while moving, at least). But the nights varied a lot, and on this one I needed extra layers in my sleeping bag.

In addition to the above I brought:

- An extra thermal baselayer. The bottoms were crucial for in the sleeping bag, since my hiking and rain pants would get very muddy. It’s also just nice to change into something clean-ish and dry after trudging through marsh and bog all day long.

- A puffy jacket. I wore this nearly every morning and evening, and also used it for extra warmth in the sleeping bag this night. I wouldn’t say it’s crucial (I met fellow backpackers who didn’t bring one), but it certainly is convenient and nice.

- The aforementioned rain gear, which saw a lot of use. Don’t go without it.

- Lightweight gloves. These weren’t really necessary, I only wore them once.

- A buff. Weighs nothing and is always useful.

For drinking water, I brought a filter (Sawyer Squeeze), water bottle and a bladder to collect water. Water was everywhere, so I never needed to carry more than a liter which helped keep my pack weight down. During cold nights, I kept my filter in my sleeping bag to prevent it from freezing (and no longer filtering properly).

Electricity

Since I was using my phone to assist with navigation (and also to take pictures), I brought a beefy 20000 mAh power bank. I also used this to charge my spot device and headlamp.

I guess normally you would be able to charge your power bank at lodges or pubs along the way, but that wasn’t really an option for me. Instead, I put my phone on battery saver and used it as little as possible. The power bank ended up having more than enough charge for the entire trip.

After resupplying at Kinlochewe, I hiked a half day with a fellow Cape Wrath Trail hiker, which was a very pleasant departure from the extreme solitude I experienced most other days. But schedules and paces differ, we parted ways and I think I spoke briefly to perhaps three people over the next four days.

After a rough few days with poor weather, I finally got to Kinlochbervie on a beautiful day. I was able to get a meal there, in the only place serving food during the pandemic. After that, I just had the actual cape to do.

Cape Wrath itself is owned by the UK Ministry of Defense, and is used as a live firing range. It’s usually inactive, but it just so happened that they had started multiple weeks of large scale exercises right before my trip. It’s obviously a bad idea to enter the area when they do this, and they fly red flags along the fenced perimeter when it is forbidden to enter the area (there is also signage near civilization).

I was in Kinlochbervie on a Friday, and called them to see whether the cape would be accessible on the weekend. The people on the other end of the line didn’t seem very well informed, but after some discussion said there might be activity on Saturday, none Sunday, and all week after that. They said I should phone Saturday morning to be sure. Of course, there’s no service near the boundary, so that wasn’t very helpful.

Since it was a beautiful day, I chose to continue on to Sandwood Bay. I relaxed there for a few hours, enjoying the sun and pristine sand. In the end I decided to walk further and camp near the boundary (approximately 6 km from the lighthouse, the official end of the trail). I looked at the weather forecast before losing cell service: 24 hours of heavy rain and wind was forecasted for Saturday afternoon. So I was hoping to get in and out the following morning.

The beach at Sandwood Bay was huge, largely empty and beautiful.

The beach at Sandwood Bay was huge, largely empty and beautiful.

I got to the boundary mid afternoon. Sure enough, I found a fence and large red flags flying at several hundred meter intervals. Other than the bay, the entire cape is desolate and boggy. Past Sandwood Bay there are no trails. Despite the beautiful weather, it was a bit difficult to find a flat, non-soggy spot for my tent. But I found one, and hoped that the flags would be taken down during the night or the next morning. Of course, I had no such luck. I woke up to ominous skies and the same red flags flying.

Leaving Cape Wrath

Leaving Cape Wrath can be difficult in the best of times, but in October the ferry across the Kyle of Durness stops running, meaning the only way to leave is to walk all the way back to Kinlochbervie (I later heard from a guy that you can arrange for the ferry to pick you up outside the summer months). Rather than sit around for 24 hours and then hike nearly 30 km in a huge storm (to the tip of the cape and then all the way back), even assuming the MOD took the flags down on Sunday, I chose to call it quits at the boundary and head back.

I was a bit disappointed to not have reached the actual endpoint. I did see the lighthouse from a distance, but it’s just not the same, you know? I got back to the beach and had a relaxed breakfast on a grassy dune by the sea. My disappointment melted away and I reflected on just how incredible the walk had been. Now all I had to do was get back to London!

It turns out that the only way to leave Kinlochbervie was by bus, which runs once a day on weekdays (I believe the schedule was decreased due to Coronavirus). It was now Saturday morning. So instead I hitchhiked to Lairg, took a train to Inverness, a bus to Glasgow, and finally a night bus to London. I was home a mere 24 hours after packing up my tent at the Cape Wrath firing range boundary.

The mountain pass between The Saddle and Bealach Coire Mhàlagain.

The mountain pass between The Saddle and Bealach Coire Mhàlagain.

The Cape Wrath Trail was every bit as good as I’d hoped. It was challenging, remote, beautiful and truly wild. I don’t think there’s a better way to experience the western Highlands.