Exploring Facebook's network

What does the (physical) network of a big internet company like Facebook look like? I’m going to try to find out. I’ll be making a lot of assumptions, loosely backed by informaton gathered from possibly out of date sources. I’ll try to be explicit when something is guesswork.

A good place to start is the traceroute tool. By default it performs reverse DNS lookups for each hop. This often reveals interesting information, and facebook.com is no exception.

For example, look at this traceroute from my VPS in Amsterdam:

$ traceroute -q 1 facebook.com

...

4 ae37.pr04.ams2.tfbnw.net (157.240.67.244) 0.493 ms

5 po111.asw01.ams2.tfbnw.net (204.15.21.124) 0.475 ms

6 po236.psw02.ams4.tfbnw.net (129.134.48.17) 0.667 ms

7 157.240.38.181 (157.240.38.181) 0.496 ms

8 edge-star-mini-shv-01-ams4.facebook.com (157.240.201.35) 0.446 ms

The first name we get that belongs to Facebook is ae37.pr04.ams2.tfbnw.net.

The domain tfbnw.net is a name that Facebook uses to name devices. The

subdomain ams2 clearly refers to the location. Typically airport codes are

used by network operators to refer to geography, and AMS happens to be the IATA

code for Schiphol–the largest airport near Amsterdam. I’m going to make a bold

assumption and guess that pr04 stands for peering router, since that’s where

the traceroute ingressed Facebook’s network. I’m not sure what ae37 stands

for, but maybe we’ll find out later.

After the peering router, we pass through three layers of devices. The first

layer is named po***.asw01, the second po***.psw02, and the third layer does

not appear to have any PTR records. These are likely colocated with the peering

router. Judging by the naming, they are probably simple layer 3 switches.

Lastly, we end up on edge-star-mini-shv-01-ams4.facebook.com, which refers to

the IP we got from Facebook’s authoritative DNS server. There are lots of

interesting bits of information to unpack here, but let’s start with “edge”.

Server deployment

Facebook has a number of large datacenters (e.g. this one), where they store huge quantities of data and perform massive amounts of computation. Datacenters are big, require a lot of power, and are very expensive to operate. It’s not cost effective to build these in the middle of a big city. So you build it out in the middle of nowhere, where land and electricity are cheap. Unfortunately, that means your servers are also far away from your users, and your users don’t like high latency.

The solution is to have much smaller deployments as close to your users as possible. For Facebook, this means putting racks of servers close to where they peer with ISPs (probably in the same building in many cases). Often, that’s in or at least very close to a major city and therefore very close to their users. My traceroute landed on the very edge of their network, the latency between the peering router and server appeared to be neglible.

A presentation1 from 2015 illustrates this concept. They call a deployment like this an “edge POP” (where POP stands for Point of Presence). According to the presentation, the benefits are two-fold. One, it allows them to terminate TCP and SSL connections much closer to the user, and thereby reduce initial latency. Two, they can cache static content, which probably saves an enormous amount of money in terms of bandwidth costs. Note that user data is probably not stored on the edge. Instead, edge machines will send RPCs to datacenters for that information.

I’d like to learn more, but Facebook’s DNS servers keep sending me to ams2 or

amt2, which are probably two different edge POPs (possibly in different

colocs). So I’m going to

enumerate Facebook’s IPv4 space, do reverse DNS lookups and see what I find.

This has the added benefit of revealing any names on devices that don’t respond

to ICMP requests. Let’s hack together a quick script to do this:

import ipaddress

import os

# Get all FB IPv4 subnets.

WHOIS_CMD = ("whois -h whois.radb.net -- '-i origin AS32934' | grep 'route:' | "

"awk '{print $2}'")

# Do a reverse DNS lookup on the address.

REVERSE_DNS_FORMAT = "dig -x %s +short"

def get_slash24s():

subnets = []

for line in os.popen(WHOIS_CMD).read().splitlines():

subnet = ipaddress.ip_network(line)

subnets.extend(subnet.subnets(new_prefix=24))

return subnets

for s in get_slash24s():

for o in range(0, 0x100):

ip = s.network_address + o

name = os.popen(REVERSE_DNS_FORMAT % ip).read().strip()

if name:

print("%s %s" % (ip, name))

This gave me a nice list of names to peruse (I’ve put the results in a gist2). There are a lot of really interesting names in here.

Since I skipped IPv6, I may be missing entire parts of Facebook’s network. I consider this to be unlikely.

Datacenters

How many datacenters does Facebook have? According to one source3, they have sixteen. Most are in the US, four in Europe and one in Singapore. Some of these are not yet operational, like the Singapore datacenter4. Can we verify these datacenters from our list of names?

In the list, I can find many names of the form dr01.prn2.tfbnw.net or

ae23.dr02.prn1.tfbnw.net. It’s highly probable that dr01 refers to a

datacenter router. The three-letter location strings do not appear to be airport

codes in this case. Grepping for unique values, we get the following list. I’ve

mapped some of them to datacenters using guesswork and ping (no promises on

accuracy); a few are still a mystery to me5.

ash -> Ashburn (Virginia)

atn -> Altoona (Iowa)

cln -> Clonee (Ireland)

eag -> Eagle Mountain (Utah)

frc -> Forest City (North Carolina)

ftw -> Fort Worth (Texas)

lla -> Lulea (Sweden)

nao -> New Albany (Ohio)

ncg (unreachable)

nha (unreachable)

odn -> Odense (Denmark)

pnb -> Papillion (Nebraska)

prn -> Prineville (Oregon)

rva -> Henrico (Virginia)

snc (western US)

vll -> Huntsville (Alabama)

Unless Facebook has IPv6-only datacenters, it appears there are 14 reachable datacenters with 11 in the US and 3 in Europe. Although reachable, presumably some of these aren’t serving yet; several datacenters on the list above are expected to launch this year.

So why are Facebook’s datacenters spread out the way they are? Instead of building an 11th datacenter in the US, why not build one somewhere in South America, Africa or Asia? Conversely, if being close to your users is not important, why not build a single colossal datacenter in the US and save on logistical costs?

The latter is easy to answer. Having a single datacenter puts you at the mercy of natural and man-made disasters. If your datacenter is hit by a hurricane, burns down or loses power for weeks, your company would risk destruction. The more datacenters you have and the more spread out they are, the less damage a single disaster is likely to do to your operations. If an entire datacenter is taken offline for whatever reason, you can continue to operate as normal; albeit under increased load at the remaining locations.

So why not build more datacenters outside the US? After all, this would probably improve latency for huge numbers of users. It would also reduce backbone bandwidth and/or transit costs. My guess is that the reason Facebook has largely neglected to do this is due to risk. A datacenter is an enormous investment, you don’t want to build one in a country only to have the local government or energy supplier renege on your deal and threaten your investment. Facebook is building a new datacenter in Singapore, so the latency and bandwidth benefits must be worthwhile. Evidently Facebook determined that Singapore was the most viable location in south east Asia, having the right combination of political stability, infrastructure and operating costs.

There’s a few more interesting things to note here. One is that there appear to

be four dr devices at most datacenters, with a few exceptions (SNC only has

two while ASH has eight, and ATN has a dangling dr08.atn1). Referring back to

the presentation1 and our original traceroute, it appears that shv refers

to Shiv, their L4 load balancer. I’m going to assume that the presence of such a

name is a good indication of whether they serve user traffic in a location.

headers-shv-00-rprn0.facebook.com.

msgin-regional-shv-01-rprn0.facebook.com.

origincache-shv-01-rprn0.fbcdn.net.

These are the only names containing shv in PRN; the other datacenters appear

to have only origincache-shv-01-rPOP0.fbcdn.net. or none at all! origincache

sounds like a service that machines on the edge use to update their cache, not

something that serves user traffic.

Does this mean that Facebook does not directly serve user traffic from their datacenters? This would imply that their edge is very well provisioned. What happens when they lose a few edge POPs at peak? Other deployments nearby would need to absorb all of that traffic in order to prevent an outage. This is only possible if they have a lot of spare serving capacity sitting around doing nothing, even under peak conditions.

That’s very expensive, so it’s more likely that I’m grepping for the wrong name or that the relevant name does not have PTR records.

The edge

So what does the edge look like? Coming back to the original traceroute, it

looks like I can search for peering routers (pr**) and names of the form

edge-star-mini-shv-[POP].facebook.com. It turns out the peering router and

edge Shiv locations largely overlap, while there is no overlap with the

datacenter locations. Some of the Shiv POP names are weird. For example AMT is

not used as an airport code but appears to refer to Amsterdam (why not use AMS

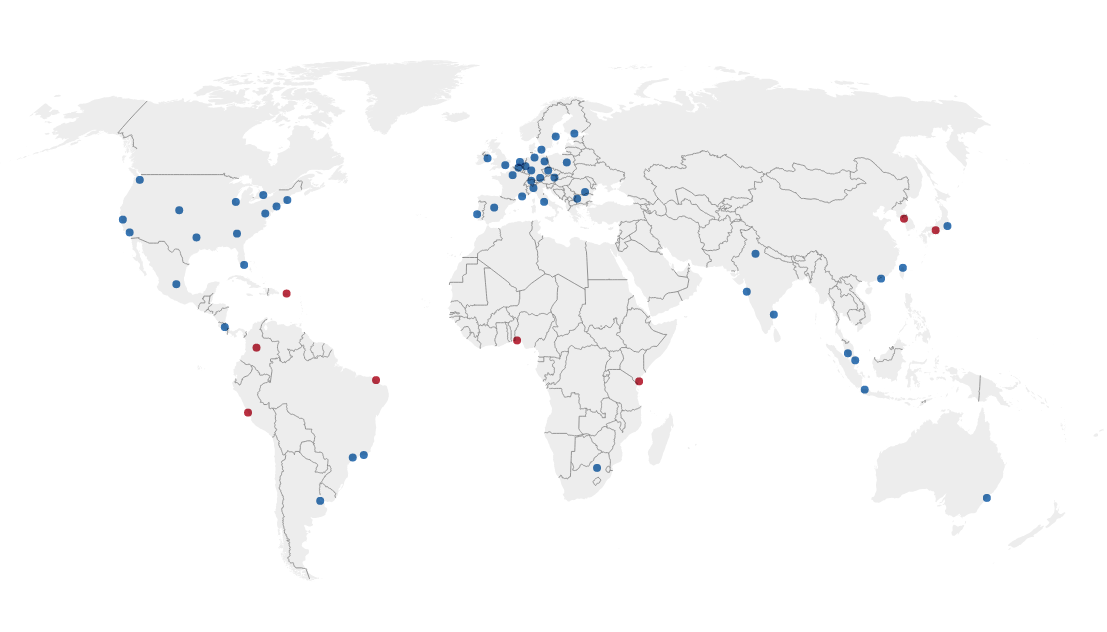

with a different number?). I’ve plotted the non-weird ones on a map (again, no

promises on accuracy!). From it, we can get a good idea of Facebook’s network

topology.

This suggests Facebook has an edge presence in 65 cities around the world, with by far the largest concentration of deployments in Europe. Locations in red refer to places where there do not appear to be peering routers, which is strange to me. If you have no peering in a location, why would you bother deploying an edge POP there? Unfortunately this is difficult to examine, since I’d need to have a machine in one of these locations. I’d be really interested to see a traceroute to facebook.com from Bogota, or Lagos. My guess is that there is peering there, but for some reason they are able to get by with a different (and probably cheaper) routing setup.

Machines in an edge POP are connected to peering by a fabric1. In AMS, it

looked like our traceroute went through 3 layers: asw, psw and an unnamed

layer which we might assume to be a top of rack switch. Examining further, the

asw layer only exists in a handful of locations; presumably those split across

multiple colocs. And it seems like every coloc has four psw switches that make

up the fabric (psw probably stands for spine switch). These switches are

likely to be connected to every rack in the coloc, in addition to the peering

routers and backbone (in the absense of an asw layer).

Can we guess how big an edge POP is? One proxy might be to look at the second

(or third, in the AMS case) layer of routing. These IPs don’t have PTR records,

but we can send a lot of traceroutes and count them anyway. Assuming a full mesh

and ECMP routing across the racks, I count 102 for ams4 and 114 for amt2. If

these IPs do indeed correspond to top of rack switches, that number seems very

high. Does Facebook really have on the order of hundreds of racks in Amsterdam?

For comparison, New York has 96, Seattle 128, Boston 29 and in Lagos I get 33.

Those proportions seem a bit skewed, especially considering that Europe has more

edge POPs which are also closer together. Perhaps my assumptions are incorrect.

Another thing I’m really interested in is how edge POPs connect to the datacenters. How does that work?

The backbone

Facebook hosts an enormous amount of user data, which will be replicated across several datacenters to avoid data loss. This necessitates a lot of data transfer between datacenters. To allow this, Facebook’s datacenters will be connected by a backbone. According to an article6 from 2017, they actually have two: an express backbone designed for inter-datacenter traffic, and an older classic backbone which is used for egress traffic. These backbones will extend to the edge where possible, so that RPCs don’t need to leave Facebook’s network.

Similar to before, we can find many names of the form ae43.bb01.ams2.tfbnw.net

or bb01.ams2.tfbnw.net, where bb almost certainly refers to a backbone

router. The two digit numeric suffix ranges from 0 to 1 or 0 to 3 depending on

the location, suggesting the routers are deployed in pairs.

The ae7 plus number prefix is interesting. I don’t see an immediate pattern to

the numbering, but perhaps this has to do with their express backbone and its

four parallel topologies (which they call “planes”). The prefix is present on

ar, bb, br and dr devices, which sounds like the structure of a

backbone. There are also some locations with bb devices that don’t have any

names with the ae prefix. Presumably those locations are still coming online.

It’s also possible that their express backbone doesn’t have any PTR records

associated with it, or that it is IPv6 only, meaning I’m only looking at their

classic backbone.

I can find bb devices in all datacenter locations and most edge POPs. For the

other edge POPs (mostly in South America, Africa and Asia), I can only find br

devices. What’s the difference between the two? Similar to the peering, this

smells like a cost saving measure. Backbone routers are very expensive; perhaps

the br devices are cheaper and less capable in some way.

Also, what does the network topology look like? Does Facebook own or lease links to all of their POPs? Or do they use transit in some places?

Here’s a traceroute to Lagos (from Amsterdam). Due to the nature of traceroute and the network’s non-determinism, I’ve cleaned it up a little.

...

4 ae37.pr03.ams2.tfbnw.net (157.240.67.242) 0.931 ms

5 *

6 ae141.ar01.ams3.tfbnw.net (157.240.34.222) 0.873 ms

7 ae23.bb01.ams3.tfbnw.net (157.240.34.174) 0.998 ms

8 ae121.bb02.ams2.tfbnw.net (129.134.46.132) 0.928 ms

9 ae520.bb01.lhr8.tfbnw.net (31.13.29.45) 11.895 ms

10 ae14.br02.los1.tfbnw.net (157.240.63.85) 98.708 ms

11 po101.psw03.los2.tfbnw.net (157.240.58.93) 99.258 ms

12 173.252.67.163 (173.252.67.163) 98.552 ms

13 edge-star-mini-shv-01-los2.facebook.com (157.240.29.35) 97.894 ms

This is interesting. First, the peering router in AMS is not directly connected

to the backbone router in AMS. It passes through an ar device first (area

border

router?).

Then we ride the backbone to London and from there directly to Lagos (undersea

cable). Lagos only appears to have br devices, but they seem to cleanly take

the role of bb devices in other POPs. Perhaps it is not necessary to have a

router here with a full internet routing table. After hitting the br device,

we pass through the edge fabric until we reach a machine.

Compare to a similar traceroute from a VPS in Toronto.

...

5 ae5.ar02.yyz1.tfbnw.net (31.13.29.62) 1.742 ms

6 ae13.bb02.lga1.tfbnw.net (157.240.35.16) 12.146 ms

7 ae2.bb02.dub1.tfbnw.net (157.240.42.178) 92.030 ms

8 ae610.bb02.lhr8.tfbnw.net (129.134.47.103) 82.153 ms

9 ae14.br02.los1.tfbnw.net (157.240.63.85) 180.759 ms

10 po102.psw03.los2.tfbnw.net (129.134.36.23) 180.802 ms

11 173.252.67.59 (173.252.67.59) 180.995 ms

12 edge-star-mini-shv-01-los2.facebook.com (157.240.29.35) 180.421 ms

In this case we ingressed in Toronto but didn’t appear to hit a peering router.

This appears to be a different peering setup, which might explain why I didn’t

find any pr devices in a handful of edge POPs. How does that work? How is an

ar device different from a pr? It appears to be connected directly to peers

in Toronto, but also the backbone routers in New York. I can find pr devices

in Toronto, but no bb or br devices. It seems like a strange setup.

Interestingly, a traceroute from Toronto to Amsterdam only ingresses in Amsterdam.

...

10 facebook-ic-331939-adm-b1.c.telia.net (62.115.148.231) 92.349 ms

11 po141.asw01.ams3.tfbnw.net (129.134.34.162) 92.938 ms

12 po236.psw01.ams4.tfbnw.net (129.134.47.225) 92.498 ms

13 173.252.67.165 (173.252.67.165) 93.312 ms

14 edge-star-mini-shv-01-ams4.facebook.com (157.240.201.35) 93.228 ms

So Facebook probably advertises most or possibly all of their IP space from every location, but isn’t aggressive about getting user traffic onto their network. If another ISP (Telia in this case) advertises fewer hops to a location, they will allow ingress elsewhere. I wonder if egress works in the same manner? Do the packets egress in AMS as well, and transit to Toronto via Telia? Or do they route asymmetrically?

Disparity

One thing that really strikes me is the relative lack of presence outside the US and Europe. However, according to this source8, the majority of Facebook users are outside these areas. India has 50% more users than the US, but get by with only 3 edge locations! And uncacheable content like your personal and friend activity is almost certainly served from a datacenter in the US or Europe. Half of the countries on this list don’t appear to have any edge presence at all.

It’s strange to me that there’s edge presence in BRU when there are five other locations within a radius of a few hundred kilometers (AMS, DUS, FRA, CDG, and LHR) with very reliable networks in between. On the other hand, the Philippines is probably served out of Hong Kong which is at least 1300 km away, while having 7 times more Facebook users than the entire population of Belgium!

This must come down to dollars. I’m sure Facebook has a lot of data showing that lower latencies correspond to increased advertising revenue. And how much revenue probably varies widely depending on geography (as estimated by this article9), meaning that an edge location in Belgium probably has better ROI than one in the Philippines.

-

Facebook’s US$1b data centre in Singapore to open in 2022 ↩︎

-

en4bz on reddit pointed out that ASH refers to Ashburn Virginia, a datacenter hotspot. Facebook appears to lease rather than own capacity here (see articles from 2017 and 2019), which is why I had trouble placing it. ↩︎

-

Building Express Backbone: Facebook’s new long-haul network ↩︎

-

musicjunky on reddit suggests the

aeandpoprefixes refer to logical interface bundles, or AggregatedEthernet and PortChannel respectively. This makes sense, as it is common to configure separate IP addresses for each bundle. ↩︎ -

How much Facebook makes, per user, per minute spent on Facebook ↩︎